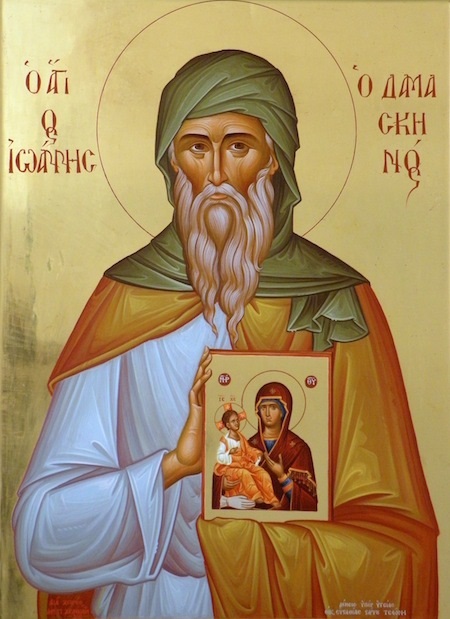

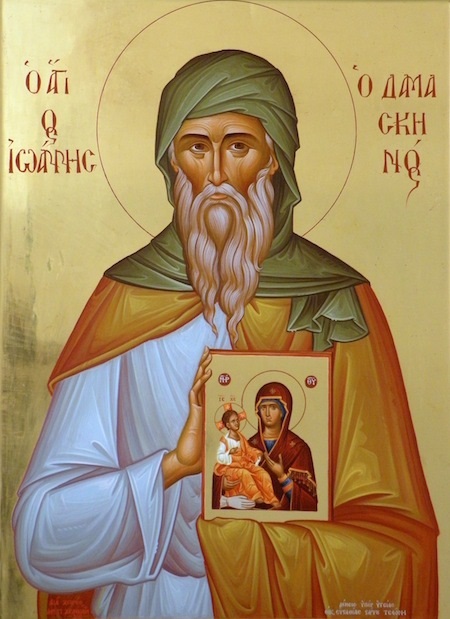

“THE WHOLE EARTH IS A LIVING ICON OF THE FACE OF GOD.”

ST JOHN OF DAMASCUS

OUR PATRON SAINT

BORN: CA. 676 AD, DAMASCUS

DIED: DECEMBER 4, 749; MAR SABA, JERUSALEM

VENERATED BY: EASTERN ORTHODOX CHURCH, ROMAN

CATHOLIC CHURCH, EASTERN CATHOLIC CHURCH,

LUTHERAN CHURCH, & ANGLICAN COMMUNITY

FEAST DAY: DECEMBER 4TH

EARLY WRITINGS

Three “Apologetic Treatises against those Decrying the Holy Images” – These treatises were among his earliest expositions in response to the edict by the Byzantine Emperor Leo III, banning the worship or exhibition of holy images.

- EARLY WRITINGS

TEACHINGS AND DOGMATIC WRITINGS

Fountain of Knowledge” or “The Fountain of Wisdom”, is divided into three parts:

1.“Philosophical Chapters” (Kephalaia philosophika) – Commonly called ‘Dialectic’, deals mostly with logic, its primary purpose being to prepare the reader for a better understanding of the rest of the book.

2.“Concerning Heresy” (peri haireseon) – The last chapter of this part (Chapter 101) deals with the Heresy of the Ishmaelites. Differently from the previous ‘chapters’ on other heresies which are usually only a few lines long, this chapter occupies a few pages in his work. It is one of the first Christian polemical writings against Islam, and the first one written by a Greek Orthodox/Melkite.

3.“An Exact Exposition of the Orthodox Faith” (Ekdosis akribes tes orthodoxou pisteos) – a summary of the dogmatic writings of the Early Church Fathers, this third section of the book is known to be the most important work of John de Damascene, and a treasured antiquity of Christianity.

1.“Philosophical Chapters” (Kephalaia philosophika) – Commonly called ‘Dialectic’, deals mostly with logic, its primary purpose being to prepare the reader for a better understanding of the rest of the book.

2.“Concerning Heresy” (peri haireseon) – The last chapter of this part (Chapter 101) deals with the Heresy of the Ishmaelites. Differently from the previous ‘chapters’ on other heresies which are usually only a few lines long, this chapter occupies a few pages in his work. It is one of the first Christian polemical writings against Islam, and the first one written by a Greek Orthodox/Melkite.

3.“An Exact Exposition of the Orthodox Faith” (Ekdosis akribes tes orthodoxou pisteos) – a summary of the dogmatic writings of the Early Church Fathers, this third section of the book is known to be the most important work of John de Damascene, and a treasured antiquity of Christianity.

- Read St. John’s Writings Here

- Against the Jacobites

- Against the Nestorians

- Dialogue against the Manichees

- Elementary Introduction into Dogmas

- Letter on the Thrice-Holy Hymn

- On Right Thinking

- On the Faith, Against the Nestorians

- On the Two Wills in Christ (Against the Monothelites)

- Sacred Parallels (dubious)

- “Octoechos” (the Church’s service book of eight tones)

St. John of Damascus was born about the year 676 of Christian parents, John Mansur (his family name) grew up in an Arab environment, in the court of the Caliph Abdul Malek. His father Sergius was a minister in the court, as were many Christians in this time of Arab domination.

John was provided with the best education available to members of the court, but his father was concerned that he be educated as a Christian. One day while walking through the streets of Damascus, Sergius saw a new-group of captives from Italy being offered for sale as slaves by their Arab captors. Among them was an old man who, upon close inspection, appeared to be a Greek monk. As a Christian and citizen of high rank, Serguis often tried to give assistance to Christians who were in difficulty. Interceding with the Caliph on behalf of the monk, Serguis brought him to his own residence to serve as a tutor to young John and his foster brother Kosmas. The monk, also named Kosmas, trained the boys in theology, rhetoric, natural history, music and astronomy. When he felt that he had taught them all that he could, the old monk asked Sergius to be allowed to spend the remaining years of his life in a monastery. Although both father and sons were sorry to see Kosmas leave, they bade farewell to him and he departed to the monastery of St. Sabbas in Jerusalem.

Sergius died suddenly and the Caliph appointed John to an important position in the government where he eventually assumed his father’s duties. John served the Caliph well and was highly respected in the count. But his comfortable life at court was quietly being challenged by the simplicity and austerity of the monastic life that had been expressed in the person of Kosmas. John could not forget his old tutor, and the wisdom and piety he imparted. Eventually, the attraction of the monastic life compelled both John and his brother Kosmas to give away their wealth and join their mentor in the Judaean desert.

About this time in Constantinople, the emperor Leo DI was in a bitter controversy with the Church over the use of icons or images. Fearing the further spread of Islam-which forbad the worship or use of images-Leo had ordered the destruction of all icons and statues representing Christ and the saints. A riot ensued as the people of the city fought to protect their churches. All appeals failed; the emperor listened to no one-neither the patriarch in Constantinople nor the pope in Rome.

Even though John was far away from Constantinople, he decided to come to the defense of the iconodules-those who wanted to keep icons in the churches. Living in an Arab Province, under the protection of the Caliph, John could speak out more clearly and forcefully than those in the midst of the controversy. He wrote three articles entitled “On the Defense of Icons”, which became the most important arguments in favor of icon veneration. The battle would last long after John’s death, but his works lived on as strong weapons in the fight:

At St. Sabbas Monastery, John retired to a cave and was placed under the guidance of an old monk who agreed to be his elder or spiritual father. The elder gave John three rules to follow: to pray to God, to do nothing because he himself wanted to do it, and to weep for the sins he had committed. Although he had long followed his own will and had been accustomed to giving orders to others, John obeyed his elder and pursued the monastic life in humility.

Knowing of John’s former position and his excellent education, the elder decided to test John to see how well he would obey. He sent him to his old city of Damascus to sell a load of baskets, but told him to sell them at an exorbitant price, one that no one would pay for such an item. John did not object, but went willingly to Damascus, the place where he once was so powerful and well known. He tried to sell his baskets, but the people laughed at him for asking such a high price. No one recognized in this thin sun-tanned monk, the important official he had been. No one, that is, but one man–John’s former servant who felt sorry to see him ridiculed in this way. The servant pretended not to know the monk and bought all the baskets from him at the price that he asked. John was able to return to the monastery, having obeyed his elder in every way.

Only once did John disobey the instructions that were his rule of life in the monastery. A fellow monk had lost his brother and could not be consoled. Knowing of John’s ability to compose music and poetry, he begged him to write a funeral hymn for his dead brother. Because his elder had left the monastery for a few days, John refused, for he had agreed to do nothing without the elder’s direction and consent. Finally, however, he felt so sorry for the bereaved monk that he consented, and wrote one of his most beautiful hymns–which has become part of the Orthodox funeral service. It begins:

What earthly sweetness remains unmixed with grief? What glory stands forever on earth? All things are but feeble shadows or deluding dreams–one moment only and Death shall take their place. But in the light of Thy countenance, O Christ, and in the sweetness of Thy beauty, give rest to him whom Thou has chosen, for Thou only lovest mankind.

The monk was very moved by the lovely hymn and thanked John for helping him in his grief. But when the elder returned and heard of John’s deed, he wanted nothing more to do with him for he had disobeyed his rule. John begged the elder to forgive him, but to no avail. The other monks also petitioned the older monk to take him back, even if it meant giving John a penance. The elder finally relented. He gave him the worst job in the monastery, and also forbid him to write any more hymns. John accepted gratefully and willingly carried out all his duties.

One night the elder had a vision. The mother of God appeared to him in a dream and said: “Why have you sealed the spring of fresh water for which the whole world is thirsty? Let it pour freely and comfort those in need. Let John praise God through his songs.” The elder then realized that he had dealt wrongly with John and hurried to him, asking forgiveness for his sternness and bluntness. He knelt and bowed low before John to beg his pardon. The talent which had been given to John could now be used to the glory of God.

John devoted himself to the composing of kanons, following in the example of Andrew of Crete. He composed kanons for many feasts, including the Nativity and Baptism of Christ, Pentecost, and Easter. His Easter Kanon is the most glorious of all hymns in the Orthodox Church; it has been called the “Queen of Kanons.” The first irmos exclaims:

Irmos: On this day of Resurrection, be illumined O People! Pascha, the Pascha of the Lord For from death to life, and from earth to heaven Has Christ our God led us, Singing the song of victory! Refrain: Christ is risen from the dead!

Arab domination

Besides the kanons, John is said to have worked on the Oktoechos, a collection of hymns in eight tones for the Sunday services. The Oktoechos was composed by Patriarch Severus of the Syrian Jacobite (Monophysite) church in Antioch in the Sixth century. John of Damascus adapted these hymns for use in Byzantine monasteries and churches. Arab domination

He also helped to establish the order of the services, using the rule that had been compiled earlier by Patriarch Sophronius of Jerusalem (634-38), according to the practice of celebrating the services at the monasteries of St. Sabbas and St. Theodosius. This rule was called the typikon; it included the calendar of feasts for the year and instructions for celebrating the feasts of special services of the Church. Through the efforts of John, this Jerusalem Typikon was revised and introduced throughout the empire.

Together with this brother Kosmas of Jerusalem (who wrote nineteen kanons, including one for the feast of the Exaltation of the Holy Cross, and the Great Kanon for the Matins of Holy Friday), John developed a method for teaching others how to sing their hymns. They introduced the practice of cheironomy–conducting or directing a choir by means of certain gestures of the hands and fingers. By teaching the monks how to sing the melodies by watching how the domestikos (the director) raised or lowered his fingers or gave signs for short melodic movements of the notes, they were able to sing together.

Both John and Kosmas were strong supporters of the true faith which they proclaimed in their hymns as well as in other writings. John- studied carefully all the writings of the Church Fathers that he could collect and wrote a very clear and concise book on “The Exposition of the Orthodox Faith.” It is a compilation of the teachings of the Church that has been acclaimed as a systematic presentation of the foundations of Christian doctrine.

Sometime before his death in December 4, 749, John was ordained to the priesthood, but he continued to live and work in his cell in the Judaean desert.